Script Writing and Rewriting

- wfavontagen

- Mar 2, 2023

- 8 min read

INT. My Bedroom – 4:13 am.

I throw a glance to a clock across the room to be sure the one on my laptop wasn’t lying. Damn. Call time to be back on set was in two hours, and I still had at least three pages to write. Saving grace: these new pages weren’t set to be shot for another three days.

I turn back to the screen, the glare of the screen burning my exhausted eyes. The scene was a nighttime bar interior with QUINN and her friends. (Hint: don’t write nighttime bar scenes… More on that later.) The unavailability of a location and the addition of a new subplot was the cause of this revision. I tap the keys and wonder how many more times I’d be rewriting this film. SPOILER ALERT: at least fifteen more times.

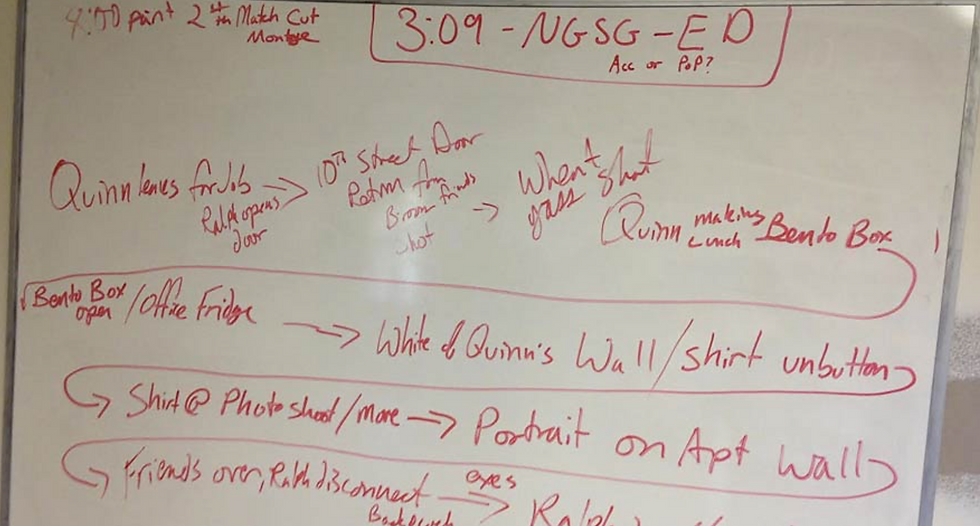

Writing the first draft of this film took place over the course of 5 sleepless days in January, 2014. I spent two months outlining the piece prior to committing it to print; but, for one reason or another, I am unable to write over an extended period of time. Rather, the deed has to be done during a woeful binge of coffee, skittles and late-night jogs. In all, the script would undergo 5 complete rewrites and 27 lengthy revisions. Even as I write this article, certain scenes are being rewritten/structured as Taylor our editor finishes the final cut.

I wrote in the first installment of this series that, while making movies was always the goal, I made the decision to pursue an English-Writing degree instead (as it is just as lucrative a career choice..). Story is paramount, telling it right is a must, and a strong script is absolutely the most important element for a film.

I’m going to say that again, because it’s surprising how often it is forgotten: Script is the most important element of a film. And while rewrites/revisions/last-minute-changes are all a part of the process, (even once filming has already begun…) entering development on a film without a super strong script in tow is asinine and a recipe for disaster, a disaster I very narrowly dodged.

It wasn’t initially the plan to begin working on a feature—it was sort of a back-up. I returned from a year in Germany in July, 2013 with a short film I had shot, and was in the back-half of the edit. Like all short film directors, I knew the film would most likely win Sundance and my career would be in the bag (Slamdance would be an acceptable alternative). To ready myself for this propulsion of fame and fortune—you’re only as relevant as your next project—I decided to begin writing a feature to have in my back pocket once the offers and deals started rolling in.

Brace yourselves. The film didn’t win Sundance. In fact, it only screened at one festival (Indianapolis), and was also snubbed by the local festival here in Boise, ID. I accept now the main issue: the 21-minute “short” German language film was just too damn long to be programmed anywhere. (Hint: let’s keep our shorts in the 8-12 minute realm).

The short did, however, help me acquire a mentor who knew a thing or two about the biz. After having the chance to pitch him the script on the Fox lot in late January 2014, he inspired me to pursue the project regardless of any outside backing or support. After giving me a few story notes, a copy of the Hollywood Screenwriter Directory and advice on casting name talent; he sent me back to Idaho to begin the seemingly endless process of rewriting development of the film.

I can’t speak too heavily on the writing/rewriting processes of others. Hemingway says it best: “writing is easy, all you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” I for one do not dislike the writing process—but rather, I dislike the process of writing. I am inexplicably jealous of other writers who enjoy laying down print, because I just don’t feel it.

Don’t get me wrong! I love HAVING written—the planning and then seeing what I’ve accomplished etc.—but for me, writing is like going on vacation. It’s fun to plan where you want to go, and once you’ve arrived it’s a good time; but finding a cat sitter, putting up with the gropers at TSA, then listening to a crying baby for ten hours on a crowded plane is just part of the horrors between coming and going.

So why do it then? Because for me, like anything this difficult, realization of the finished product is rewarding and contagious beyond compare.

Between the completion of the first draft on January 15, 2014 to the first day of principal photography on July 22, 2014, the script went through 3 complete rewrites and about 19 revisions. About 85% of the story from the original draft had been removed or altered. Initially, the main love interest in the film was comprised of four sub-characters who were eventually combined to create the lead role of Quinn, played by Jessica Sulikowski. (More on working with Jessica to create Quinn in future post.)

Later—after the first few rounds of editing the actual footage—we went back to some of the earlier drafts of the script and re-inserted characters, plotlines and scenes that were tossed months before production. We then produced these new script pages four months after principal photography, and brought the story back to about 60% of the original draft.

I’d like to say this is unusual. While it certainly is not the most efficient way to write and produce a script, there is a lot to be said for being willing to make big changes when you realize things aren’t working. James L. Brookes is notorious for rewriting and reshooting endings up to eight times after the fact. While my push to set and keep a shoot date may have put things in a pinch time-wise, there is nothing like a hard deadline to make sure things are done—because honestly, you’ll never be fully ready for it when it hits.

In hindsight, after going through development, pre-production, production hick-ups, hours of editing, and the pick-up process, here is a light listing of things I learned and will take with me into the next script. Especially if we are talking low-budget. Some of these may seem obvious now, but during the first few drafts my mind wasn’t even thinking this way.

Have as many scenes take place in the daytime as possible. The first draft of the script was night-shoot-city. In Boise during the summer, the sun sets at 11pm and rises at 5:30am. It’s stressful, wears out your crew, and you have very little control and options over your environment. Even if you are shooting interiors and are faking day-for-night, the lighting scenarios will eat up your set-up times. What’s worse, when it’s 99 degrees outside and you have all your windows blacked out with 4000 watts of artificial lighting and the AC turned off for sound reasons… You can imagine the enormous discomfort of your crew—especially when you have to cut mid-take because sweat is pouring down the actors’ faces.

Don’t set the scene. Turns out there is nothing more boring than watching the characters walk into an empty room, sit in their respective seats, then banter for a moment on non-plot related subject matter before getting into the juice of the scene (same goes with exiting). I made the mistake of both writing and shooting several scenes this way, and after my editor had his way with it, turns out a total of 10 minutes of precious screen time had been wasted on this. TRICK: Find the line of dialog where the drama starts, and cut immediately to that. Your audience will fill in the gaps for you.

Don’t write scenes that take place in cars. They are boring, unoriginal, and nightmares to shoot. You have very little control, the sound quality will be terrible, and there really aren’t that many ways to get an interesting shot of the actors.

Don’t write scenes that take place in bars. Or at a wedding. Or at a gala. Or at a funeral. I did all of these, and while it seems so glorious on paper, these shots were inexplicably difficult to pull off. On the production design side, yes, they are large locations that need to look interesting and real. But the real challenge is filling the scene with extras, because that is what will really sell or destroy the reality of the scene. It’s an indie, so there is no budget to hire professional extras, and until someone has set experience, they will never understand exactly how long everything will take. Three hours in, extras begin dropping out like flies, and you aren’t even half-way done. These extras also have to be directed , because surprise!—people actually move around in bars and at galas. They also have to do so the exact same way for every take, and aunt Carole can only pretend to bump into uncle Bob so many times. Also, all these venues typically call for nighttime. I think you get the point.

Keep it moving. I came to learn there is rarely a need for a scene to last longer than a page and a half at the most. Keeping the things I mentioned in #2 in mind, it tends to be the case. Sure, it doesn’t apply to ALL scenes, but generally if it feels too short when you read it back, it isn’t.

Write for an environment that will allow for good blocking. For me as a director, blocking is everything. Especially if the scene is dialog heavy, the last thing I want to shoot (or see as an audience member) is a boring space with the camera simply cutting back and forth on the coverage of the actors sitting and yacking. This is why I love Woody Allen so much—his blocking is phenomenal, as are his ‘oners.’ His films are generally very heavy in dialog, but allow for a space in which the actors and camera can dance about, letting the scene stay physically and visually active. So again, avoid writing scenes in a bathroom, or on a roof, or any other restrictive environment.

Workshop. Have someone else (the more the better) read it and actually listen to their feedback. This is so important, especially several drafts in when you might be becoming oversaturated by the material and risk losing perspective. This is a tough one, because it will take you a while to find people you can trust to give GOOD advice, but I would definitely run by past as many eyes as possible, and the sooner you allow yourself to accept criticism, the better your craft will get. This is probably where my writing degree has helped me the most—after hours and hours of reading and listening to your peers’ criticisms, you really lose your sensitivity towards the process.

Writing Almosting It was a fantastic learning opportunity for me, one that really began with a 30 page short story I wrote at the University of Nevada in my Junior year. To see a character I created become embodied by The Six Million Dollar Man and locations I grew up in become the venue for a make-believe-world-made-real has been incredible.

When I write about keeping things to scale—not shooting in bars, etc.—I mean more so that one should write with budget in mind. Should you not write that scene because I say so? No way. Would I do it again? Absolutely. But understand the consequences for what you put to page, and be prepared to deal with it. Much of the revisions of the initial draft came about as a way to bring the picture to a more manageable production.

I held on to my gala scene, as well as my wedding scene, but these were really just the tip of what the first draft called for. These scenes—in theory—should not exist for reasons I mentioned. Our budget should not have permitted it. It was because I had such a fantastic crew of irreplaceable talent—all found locally here in little Boise, ID—that allowed the vision to come to life. I am grateful to have had the team I did. I hope they can all be as proud as I am—that together we gave birth to words I once slapped furiously on a keyboard late one night with hot coffee by my side and a fist full of Skittles keeping me going.

Comments